|

|

Contextual Learning Portal A Circle of Parks: Boston Parks and Greenspace as a Case Study for Civic Engagement

Basics- Project TitleA Circle of Parks: Boston Parks and Greenspace as a Case Study for Civic Engagement

- OverviewThis project presents a series of lesson plan modules related to the Southwest Corridor Park and the Emerald Necklace Park System in Boston.

The goal of the Southwest Corridor Park youth & family programming is to "nurture a next generation of park leadership" for the Southwest Corridor Park, and through this goal, to also encourage all types of civic engagement, for parks, environment and other community needs.

This curriculum provides a resource to support students in classrooms and in summer and after-school program to learn about the role of civic engagement in creating and caring for parks and greenspaces. Using videos, readings, online research, and a variety of possible extension activities the curriculum is designed as a resource for a variety of classroom and youth program settings. -

- Project Sponsor OrganizationSouthwest Corridor Park Management Advisory Committee (PMAC)

- Target Grade LevelMiddle School and up

- Duration of projectFive lessons plus extension activities

- FormatMay be asynchronous or teacher-led; intended to be adaptable for remote or in-person learning.

- Materials Needed- Internet access to view videos and readings [or download videos to a computer for off-line viewing];

- Journal for writing and drawing;

- Virtual or physical classroom; or access to lesson website for self-paced study;

- Optional for in-classroom workstations: For the inquiry lesson, a printed copy of the collection of primary and secondary source materials;

- Optional for in-classroom map activity: Paper copies of park maps.

Lesson #1 | The Geography of Parks & Greenspace in Boston- Lesson 1 TopicThe Geography of Parks & Greenspace in Boston

- Lesson 1 Objectives[1.] Students will be able to define greenspace, playground, parks

[2.] Students will be able to analyze data to compare parks and greenspace in Boston and other cities

[3.] Students will be able to describe the "Circle of Parks" made up of the Southwest Corridor Park and the Emerald Necklace Park System.

[4.] Students will be able to identify other parks and greenspaces in their communities. - Lesson OpeningThis series of lessons focuses on parks and greenspace in Boston as a case study in civic engagement.

First, sometimes it is useful to define everyday words that we use all the time. In this exercise we will define these three terms: park, playground, and greenspace.

Use the attached worksheet to develop a definition for these three terms. -

View/Download File: Define Park Greenspace and Playground - Readings and VideosWatch the "Circle of Parks" video.

INTRODUCTION: In the following video, you will see how some of the parkland in the city of Boston was created over a period of more than one hundred and fifty years. In cities like Boston, the decision to set aside land for greenspaces and parks happens gradually over many years, with many different people involved in making decisions about how land will be used.

Circle of Parks - Video 1 - Boston Parks as a Case Study in Civic Engagement from Southwest Corridor Park on Vimeo.

-

View/Download File: Video Script - A Circle of Parks Web Link: Boston Parks as a Case Study in Civic Engagement (Circle of Parks Video #1) - Introduce Data Analysis ActivityAs cities grow, more and more land is used for buildings, roads, parking lots and other human-made features of the city. It takes thoughtful planning to set aside or reclaim land for parks and greenspace.

Some cities, such as Savannah, Georgia, were carefully designed from the beginning to include a system of neatly-laid out streets with small parks spread throughout the downtown area; or, here in Massachusetts, Lowell, Massachusetts, designed as a mill city, laid out with canals, streets and a town commons as greenspace in the center of the city.

Other cities, such as Boston, take shape gradually, with decisions about parks, roads and buildings made by many different groups of people over many years.

Ask the following hypothetical question: If you had the opportunity to design a whole city, how much land would you use as parks and greenspace? Fill in the blank: in my ideal city, __% of the land would be used for parks and greenspace, and everyone would live within a __ minute walk of a park. In the following activity you can look at statistics for Boston and other cities. - Data Analysis ActivityThe Trust for Public Land (TPL) analyzes and scores park systems in the 100 largest U.S. cities, based on four characteristics of an effective park system: Access, Investment, Acreage and Amenities. Go to the TPL website to see Boston‘s ParkScore:

https://www.tpl.org/city/boston-massachusetts

Find data for Boston. Discuss with the class, or write in your journal, to answer the following questions:

[1.] How does Boston rank overall? The ParkScore is a number from 1 to 100, with 1 as the best city among the 100 largest cities in the United States.

[2.] How does Boston rank for the four characteristics that are included in the ParkScore: Acreage, Access, Investment and Amenities? (On the website, mouse over the "I" icon to see the definitions for these four terms.) These rankings are based on percentiles, with 99 as the best. A percentile ranking of 50 means that the city ranks better than 50% of the other cities; a percentile ranking of 75 means that the city ranks better than 75% of other cities; a percentile ranking of 99 means that the city ranks better than 99% of the other cities, on that characteristic.

[3.] Is there any data that surprised you?

[4.] Why do you think the Trust for Public Land use these four characteristics (Access, Investment, Acreage and Amenities) to analyze park systems?

Activity: Compare Boston to another city in the United States. Use the attached cognitive organizer: "Worksheet - Comparing Cities / Park Scores / From TPL Website" -

Web Link: Boston, Massachusetts | The Trust for Public Land View/Download File: Worksheet - Comparing Cities / Park Scores / From TPL Website View/Download File: Filled In Sample - Comparing Cities / Park Scores / From TPL Website - Map Reading ActivityExamine maps online or in printed versions to study the geography of parks and greenspace in Boston, and in your own neighborhood or community. Using the Emerald Necklace map plus one of the other maps listed, answer the following questions:

[1.] Look at the Emerald Necklace map: Which of the park(s) featured on the Emerald Necklace map are closest to your school? To your house?

[2.] Why do you think this park system in Boston is called the Emerald Necklace?

[3.] Look at a map of all of the parks in Boston or in your neighborhood or community. What parks are closest to your home?

[4.] Look at the shapes of the parks on your map. Some are linear parks, stretching over a long distance like a pathway through the city. Others are more like squares and rectangles. Do you see any parks that stretch along a body of water, or along a train or subway line, or are defined by other natural or human-made features of the city?

[5.] Which parks have you visited? -

Web Link: Emerald Necklace Map Web Link: Boston, Massachusetts | The Trust for Public Land (Citywide Park Maps) Web Link: City of Boston Parks and Playgrounds (map and directory) Web Link: Massachusetts State Parks / Interactive Map - Lesson ClosingWrite or draw a reflection in journal.

- Vocabulary / Word WallPark

Playground

Greenspace

Acreage

Investment

Access

Amenities

Ranking

Percentile - References / Resources / Teacher PreparationBrowse the Southwest Corridor and Emerald Necklace websites for background information about these parks.

-

Web Link: Southwest Corridor Park Web Link: The Emerald Necklace

Lesson #2 | Concepts for Civic Engagement- Lesson 2 TopicConcepts for Civic Engagement

- Lesson 2 Objectives[1.] Learn key terms from economics: Public Goods, Private Goods, Public Sector, Private Sector, Non-Profit Sector

[2.] Think about how and why community leaders can advocate for public parks and other important public resources.

[3.] Understand the concept of public goods and recognize the roles of the public sector as well as the roles of individuals, private businesses and community organizations in supporting public goods such as parks and greenspace.

- Lesson OpeningOpening question -- What are some of the basic services that the city government provides?

- Readings and VideosWatch the Video: The Economics of Public Goods.

(Video script included below and in the appendix.)

Economics of Public Goods - Video 2 - Circle of Park Series from Southwest Corridor Park on Vimeo.

-

View/Download File: Video Script - The Economics of Public Goods Web Link: Economics of Public Goods (Video #2) - Video Follow-up Activity #1Look at photos of a city street or take a walk along a city street and make your own list of things that you see. How many public goods can you find in your list? Can you include things that are invisible, such as clean air or shade from trees? Can you include some things that are taken for granted such as signs and traffic lights? Who in the community takes care of these things?

- Video Follow-up Activity #2Public parks are sometimes taken for granted, but these are important public goods that need the support from the community. As a class discussion, "fishbowl" discussion or journal writing activity, explore the following questions:

(a.) Suppose that you are a city councilor working on the budget for the city government. You want the city to spend more money to support a park in your neighborhood, to fix benches and update playground equipment and to add more trees and flowers. How can you convince others that the city should provide money for this park, as an important public good? What are some reasons that other city councilors might not want to spend more city money on park improvements?

(b.) Suppose that you are a member of a park volunteer group, speaking to local neighborhood group to ask for help with park improvements. The neighborhood group includes residents who live near the park, plus people who own or manage small businesses near the park, including a local bank manager, a restaurant owner, and a childcare center director. How would you convince people to donate volunteer time or money to improve the park? What would motivate people to want to get involved? What reasons might people give for not getting involved?

(c.) How much of the support for improving this park should come from the city budget and how much should come from community volunteers? - Lesson ClosingWrite or draw a reflection in journal.

Reflection Ideas:

[1.] Many people volunteer in their communities, providing public goods or beneficial services, such as helping with parks and greenspace, helping to protect clean air and water, or volunteering to help with youth sports programs, arts programs or other beneficial programs. Why do people volunteer? What motivates them? How do people benefit from being a volunteer?

[2.] Why are public parks and playgrounds considered to be public goods, while indoor gyms and sports facilities, which also provide space for recreation, are private goods? What is the difference? Could a park or greenspace be a private good? (Think of a private golf course, private campground, or other private outdoor places.) Why is important that parks and greenspaces are generally provided as public goods? - Vocabulary / Word WallPublic goods

Private goods

Public sector

Non-profit sector

Private sector

Informal organizations

Lesson #3 | History of the Southwest Corridor Park - Inquiry Lesson- Lesson 3 TopicHistory of the Southwest Corridor Park - Inquiry Lesson

- Lesson 3 Objectives[1.] Use primary and secondary sources to learn about the history of the Southwest Corridor Park.

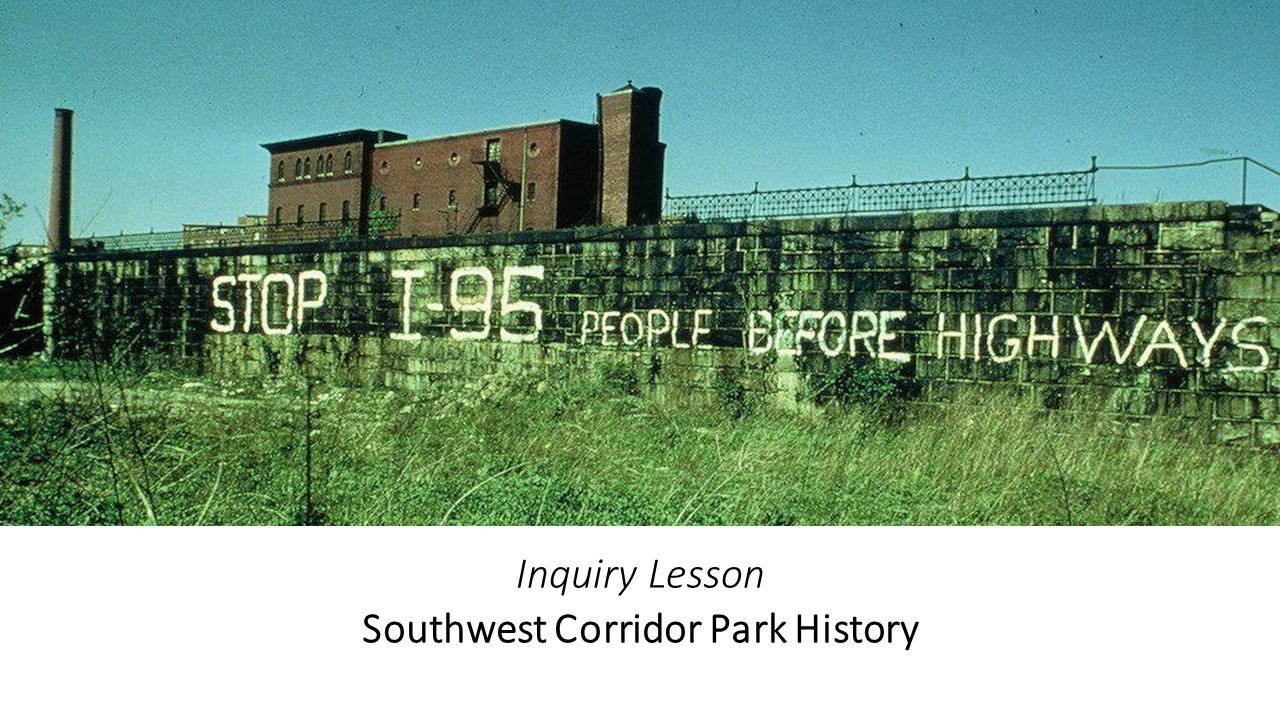

- Lesson OpeningPresent the photo "Stop I-95" and ask students to think about what they see in the photo, make guesses about the story behind the photo, and think of questions they would like to ask about the photo.

-

- Inquiry Activity

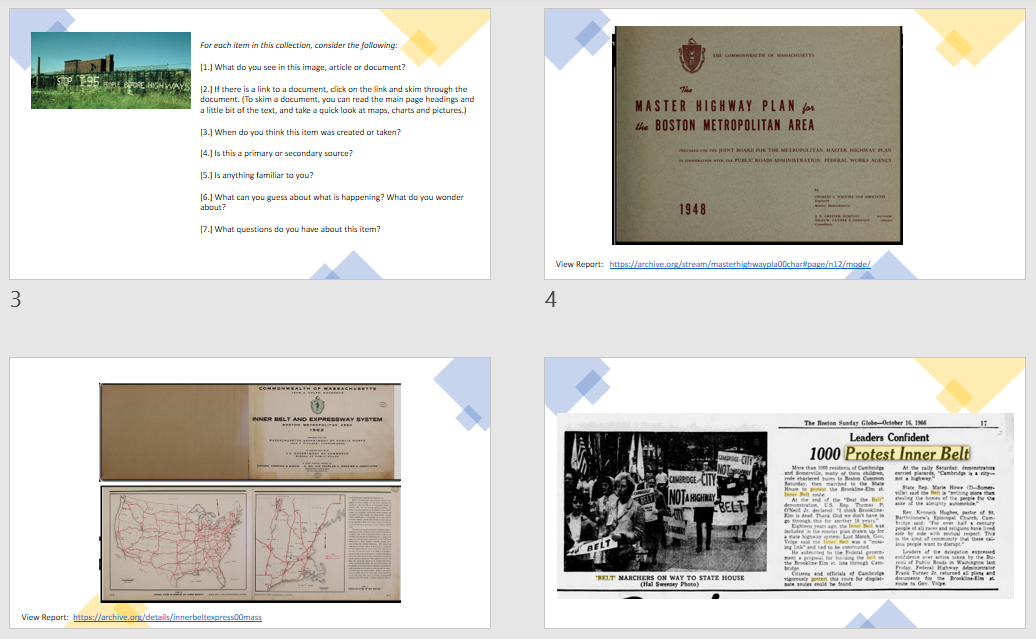

Using the following collection of primary and secondary sources, students look at photos, skim printed materials, and make lists of their observations and questions about each item.

Inquiry Activity (PowerPoint)

For this inquiry activity, students can work independently or in small groups, online or in a physical classroom.

(Option 1 .) Students go to the slide presentation. [Teachers may edit the slide presentation to focus on specific materials.]

(Option 2.) In a classroom, set up stations with three or four of the primary sources at each station and allow students to travel from station to station.

(Option 3.) Create collaborative groups and ask students to choose a mix of 5-8 photos or primary sources from the slide presentation.

[See the links at the end of this section for direct links to each of the items in the slide presentation.]

For each item in this collection, students consider the following:

[1.] What do you see in this image, article or document?

[2.] If there is a link to a document, click on the link and skim through the document. (To skim a document, you can read the main page headings and a little bit of the text, and take a quick look at maps, charts and pictures.)

[3.] When do you think this item was created or taken?

[4.] Is this a primary or secondary source?

[5.] Is anything familiar to you?

[6.] What can you guess about what is happening? What do you wonder about?

[7.] What questions do you have about this item?

-

View/Download File: Southwest Corridor Park - Primary and Secondary Source Materials Web Link: Jamaica Plain Historical Society - People Before Highways Web Link: Southwest Corridor Park / Park History Page - Inquiry Activity / Report-OutStudents share their observations and questions with the class, and develop an overall list of all the questions that these items raised. Write all the student questions down in a shared space (whiteboard, chat, virtual whiteboard) and then categorize them. The teacher facilitates this process by helping students create categories. Give students the opportunity to ask more questions and piggy-back off other students’ questions during and after categorization.

- Extension / Further Research / Multi-day Research Work(Individually or in small groups, students can pursue further research)

Individually or in groups, students use questions as jumping off points for individual or small group research project. Student(s) decide what question(s) they want to explore, even adding additional questions or topics. Students should create a guiding question for their research. The teacher’s role is to facilitate the process by providing support, offering suggestions, and challenging assumptions. Provide students with resource links, with the understanding that they may also find additional websites, photos, primary and secondary sources. - Lesson ClosingWrite or draw a reflection in journal.

Reflection Ideas:

[1.] The best stories from history emerge after pulling together clues from many different sources, such as old maps, flyers, newspapers or photos. What are some of the sources that can help to tell the history of a park, a neighborhood, or a city? How do these items get created and saved? - Vocabulary / Word WallPrimary source

Secondary source - Resource LinksLINKS:

-

Web Link: Mapjunction.com: Boston - Historical maps compared with Maps of Today (Search for 1962 Inner Belt Key Map) Web Link: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center / Breathing Room Exhibition / People Before Highways Web Link: Southwest Corridor Park / Bookshelf Page

Lesson #4 | Who Takes Care of the Parks?- Lesson 4 TopicWho Takes Care of the Parks?

- Lesson 4 Objectives[1.] Students will be able to read and gather information from an informational text

[2.] Students will be able to identify different entities that maintain and manage the parks, greenspaces, and open spaces

[3.] Students will be able to develop strategies for involvement in parks, greenspaces and open spaces.

- Lesson OpeningWe have seen how communities and individuals act with agency to make change. What does the word agency mean in this context? What are other definitions of the word agent or agency?

- Readings and Videos / Part 1Read Essay: Understanding Civic Engagement

Reading: Understanding Civic Engagement (with FIVE MYTHS)(PDF)

Audio Recording (As Video) - Understanding Civic Engagement

Watch video: Understanding Federal, State and Local Government

Understanding Federal, State and Local Government - Video 3 - Circle of Park Series from Southwest Corridor Park on Vimeo.

Look at annual report: Southwest Corridor Park annual report (written report and PowerPoint presentation) (2019) -

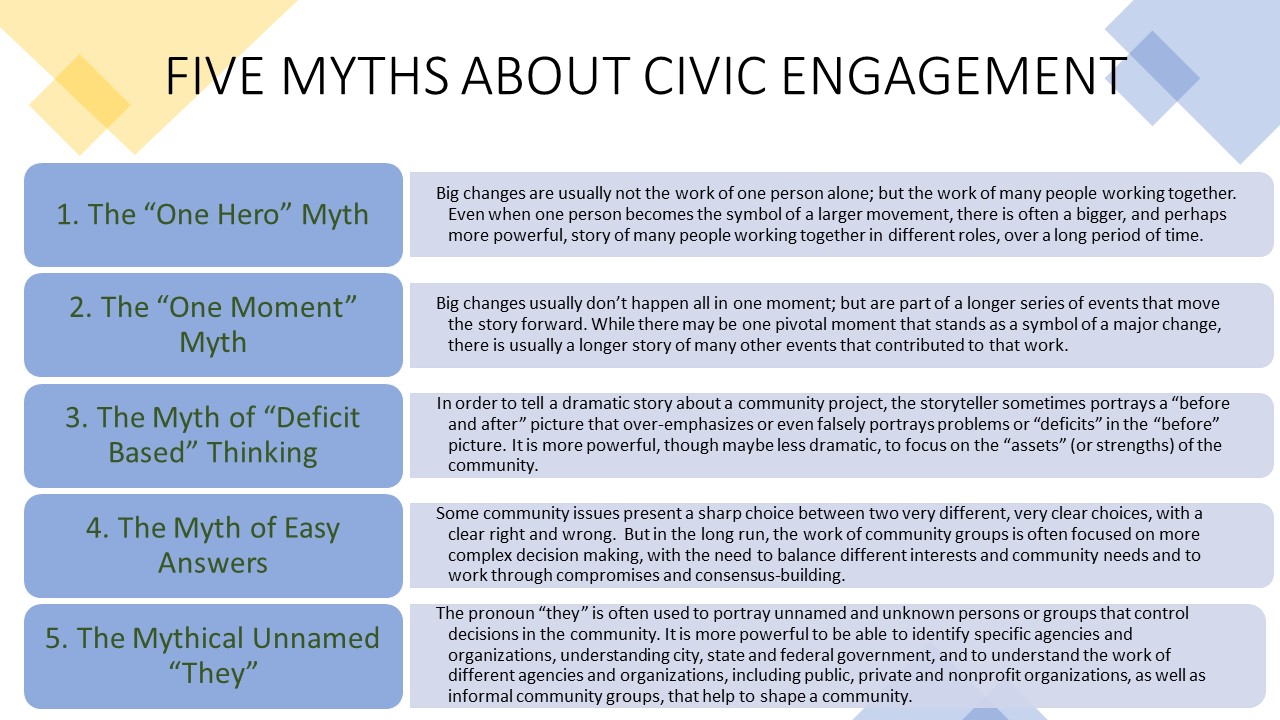

View/Download File: Video Script - Federal, State or Local Web Link: Southwest Corridor Park - 2019 PMAC Annual Report Web Link: Understanding Federal, State and Local Government (Video #3) View/Download File: Reading - Understanding Civic Engagement View/Download File: Understanding Civic Engagement (Audio Recording) - Exercise: Myths and Realities Using the "Five Myths" list from the reading, write a list of "Do`s and Don`ts" or "Myths and Realities" about civic engagement.

- Discussion/Reflection: Whose Vision Created the Emerald Necklace?Using the three examples of Emerald Necklace histories in the reading, discuss or write in journal: whose vision shaped the Emerald Necklace? What differences did you notice in the three ways of explaining the history?

- Readings and Videos / Part 2Read websites: Who manages the parks? Choose one park. This may be the Southwest Corridor Park; the Emerald Necklace overall or a specific park within the Emerald Necklace such as Franklin Park, Jamaica Pond or Charlesgate; or a park in your neighborhood or community. Study the relevant websites for this park to learn the names of the city, state or federal agencies that manage the park and the names of any community groups that support the park. You will use this information in the exercises below.

Several websites are linked below. There are also many other park volunteer networks in Boston and beyond. -

Web Link: Southwest Corridor Park website Web Link: The Emerald Necklace Conservancy website Web Link: Charlesgate Alliance website (part of Emerald Necklace) Web Link: Franklin Park Coalition website (part of the Emerald Necklace) Web Link: Friends of Clifford Park website Web Link: Friends of the Mary Ellen Welch Greenway website – A community group that supports East Boston`s green spaces - Exercise: Park Management ChartBased on the website(s) you visited, choose one park: the Southwest Corridor Park, one of the Emerald Necklace Parks, or a park of your choice in your neighborhood or community. Create a chart showing the public (governmental) agencies that manage the park and any non-profit organizations or neighborhood organizations that support the park.

- Vocabulary / Word WallPark Friends Group

Conservancy

Advisory Board

Agency

Agent

Civic Engagement - Lesson ClosingWrite or draw a reflection in journal.

Reflection Ideas: [1.] At different times in history, there have been many different ways of deciding who owns, manages and cares for shared, public land. In contemporary Boston, city and state parks agencies own and manage parkland, often with community groups that help to care for the parkland. Thinking of earlier times in Boston`s history, how did the indigenous people in Massachusetts steward land? How did the early English settlers take care of Boston Common? [2.] What motivates people to voluntarily contribute time or money to help take care of public, shared land?

Lesson #5 | Decision Making- Lesson 5 TopicDecision Making

- Lesson 5 Objectives[1.] Students will be able to evaluate different points of view and objectives when making decisions regarding parks, greenspace, and land use.

[2.] Students will be able to model consensus building and compromise in decision making.

[3.] Students will be able to describe approaching for listening to and valuing a diversity of community voices. - Lesson OpeningReview vocabulary and concepts related to decision making in civic engagement.

- Case Study ExercisesStudents work individually or in small groups to analyze three case studies.

-

View/Download File: Decision Making - Case Studies View/Download File: Decision Making - Case Studies - With Sample Filled-In Charts - Lesson ClosingWrite or draw a reflection in your journal.

Reflection Ideas:

[1.] In a community with many people of different ages, incomes, races, languages and ethnicities, do you think it is sometimes hard to make sure everyone`s ideas are heard? Explain your answer. How can a community leader try to make sure that everyone`s opinions are heard?

[2.] How would you define "participatory democracy?" Here are some ideas to get you started. In small towns across the United States, there is a long tradition of local "town meetings" or "town halls" in which community residents vote on the town budget and on town rules and regulations; on questions as big as whether to build a new park or as small as what type of snow-melt the town should use in the winter. In larger cities, decisions are made by a mayor and city council, who are elected by the voters. However, voters and residents in cities also have an opportunity to comment directly on many specific decisions through public meetings and through "ballot questions" that are voted on on election day. For your reflection: How can communities make sure that democratic decision making is more than a quick meeting, a vote, and going with the majority of votes? In other words: how can "participatory democracy" make sure everyone gets to participate? - Vocabulary / Word WallMajority Rule

Consensus

Compromise

Public Meeting

Public Process

Democracy

Participatory Democracy

Lesson #6 | Extension Activities- Lesson/TopicExtension Activities

- Extension Activities: Exploring Park-Related CareersDiscuss: Suppose that you were going to work for a local parks department or volunteer with a local park. What role(s) would you want to play? For example:

* Professional park maintenance – repairing equipment, taking care of trees and gardens, cleaning, supervising other staff

* Volunteer park maintenance – gardening, building hiking trails, painting signs, clean-ups

* Design – designing playgrounds, landscaping, gardens, etc.

* Informational – designing park maps and brochures

* Activities – being a tour guide, organizing park activities, teaching people about the park

* Safety – providing public safety in the park; developing park rules; creating signs

Research: Choose a park-related career and use the Massachusetts Career Information System (MassCIS) or other resources to learn about that career.

Here are some examples of careers that are either (a.) directly park-related, such as park ranger or playground designer, or (b.) indirectly related, such as climate scientist, law enforcement officer, GIS/mapping technician, or youth sports instructor, by providing research, planning, public services or community activities relevant to parks.

Arborist

Civil Engineer

Climate Scientist

Community Organizer

Concert/Performance Producer

Environmental Educator

Environmental Engineer

GIS/Mapmaking Technician

Historian

Horticulturalist

Landscape Architect

Landscaper

Law Enforcement Officer

Park Interpreter

Park Manager

Park Ranger

Playground Designer

Tourguide

Youth Sports Instructor - Extension Activities: Concluding ProjectsConcluding Projects: Choose a local park or a section of the Southwest Corridor Park or Emerald Necklace and develop a product such as:

* a park map

* a playground design

* a garden design

* a container garden or indoor garden

* a nature journal

* information for park tour guides

* a park brochure

* a history or timeline about the park

* a video, podcast or slide presentation about the park

* a photo journal about the park

CONCLUSION: Share projects with classmates, the school community and the park volunteer groups and neighborhood associations who support the park you focused on. -

- Extension Activities: Civics ProjectsThe Circle of Parks Module may be used as a springboard for Civics Project as detailed in the Civics Project Guidebook.

- Lesson ClosingReflection Journal:

Parks and greenspace are just one of many resources that communities need. By studying parks and greenspace, you learn about many aspects of civic engagement. Some of the same ideas can be applied to all kinds of community resources, such as schools, roads, public transportation, shopping, and more. The more you learn about these topics, the more you learn about ways that citizens can get involved and about how different careers fit into creating strong communities. Write a brief reflection about the role of civic engagement in supporting parks and other community resources.

Appendix- Video #1: Circle of Parks

Video Script #1: A Circle of Parks

Imagine that you had the chance to design a whole city. Think of a city like Chicago, Altanta, Savannah or Boston. What would you put in the city? You might think first of buildings, homes, schools and roads. Subways and buses to help people get around. Bridges to travel over rivers. Places to buy food. Places to shop. Places to park cars. The city will need systems for water supply, electricity, and phone communications. A sewer system to take away wastewater. In a healthy city, all these systems are in balance. The city is busy with people working and living and traveling but there is also room for parks and greenspaces where nature can have a home in the city.

The city of Boston has a circle of parks and greenspace that stretches from the Downtown Boston area to the neighborhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury and Jamaica Plain, to Brookline and Back Bay, and to the South End and the Fenway neighborhoods.

This circle of parks is made up of the Emerald Necklace and the Southwest Corridor Park.

The Emerald Necklace is a string of parks, from Boston Common to the Public Gardens to the Back Bay Fens, Charlesgate, Riverway, Olmsted Park, Jamaica Pond, the Arnold Arboretum and Franklin Park. Through this string of parks, you could travel from the Franklin Park Zoo, then through the parkland of Franklin Park, through playgrounds and picnic areas, past the sailboats on Jamaica Pond, and along the water in Olmsted Park, and continue through this string of parks until you arrive at the Swan Boats in the Public Gardens. Through all the Emerald Necklace parks, you notice Olmsted’s style, with paths travelling through trees and fields, and with arched stone bridges to cross as you walk along ponds and streams.

On the other side of this circle of parks, the Southwest Corridor Park is a 4-mile linear park that runs along the path of the MBTA Orange Line, with bicycle and walking paths, playgrounds, spray pools, basketball courts, tennis courts and gardens. On the Southwest Corridor Park you can travel from Forest Hills MBTA station to Back Bay MBTA station, and along the way you will see neighbors gardening; people walking their dogs; people bicycling; skateboarders skateboarding; children playing; and of course the Orange Line trains passing by.

The Emerald Necklace was designed in the 1800s, specifically because people wanted a better city, and they were thinking about what they wanted as the city was growing bigger and busier and the water was becoming polluted. Along the edge of the growing city, there was land that was marshy, and those marshes were polluted by wastewater and sewage from the city. The air around the marshes smelled worse and worse each year. Citizens petitioned the local government, demanding that the government address the pollution and asking that the city start to build a system of parks. The city government responded, and commissioned plans to re-channel that water from the marshes, and to create a system of greenspace and parkland, which became the Emerald Necklace.

The Southwest Corridor was built in the 1980s, with a similar story. In the 1950s and 1960s and 1970s, more and more cars were coming into the city of Boston each day. At the same time the whole country was growing, and the federal government was developing plans to build new highways throughout the country. The federal government proposed to build a highway system through the middle of Boston, and worked with the state government to provide money for the highway, to start planning, and even to start taking down houses and buildings to make room for the highway. But people in the neighborhoods protested, and eventually the governor of Massachusetts stopped the plans for the highway.

Instead, the Southwest Corridor Park, and a new route for the MBTA Orange Line, were built along the path that would have been the highway. At that time, the MBTA Orange Line had an old system of elevated trains and needed to be re-built. After lots of planning, all the groups agreed to build the subway line, and parkland, and a bicycle path, along the route that was going to be the highway. At the time, this was a huge decision, and this project was the first time that federal transportation money was used to build subway and bicycle transportation instead of roads and highways.

Who worked on these projects? In both cases, the idea for the parkland came from citizens, responding to a rapidly growing city and building greenspace into the urban environment. The design of the Emerald Necklace came from the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted Park, one of the Emerald Necklace parks, was named for him. Olmsted was one of the first landscape architects in the United States. When the city of Boston decided to create a system of parks, they commissioned Olmsted to be the designer. Olmsted had already designed Central Park in New York and other successful parks, after studying and developing design ideas along with other architects in the United States and in Europe who were learning about how to preserve nature and provide parkland for people in modern growing cities.

The design of the Southwest Corridor Park was the work of literally thousands of meetings, with input from neighborhood residents from each neighborhood along the park.

The people from the neighborhood groups who had protested the highway wanted to be part of the planning for the new park. The state government agreed. When the state government hired engineers and architects for the design team, they agreed that the design team should have meetings with the neighborhood residents to plan the park. So the design team organized seven Station Area Task Force (SATF) groups, with one for the neighbors near each MBTA transit station that would be along the new path of the Orange Line. An advisory group, called the Parkland Management Advisory Council (PMAC) also helped with overall planning for the whole park. (PMAC still exists and created this video.)

Because of those meetings, the park has different features in each neighborhood. The people in some neighborhoods were especially eager for gardens; some wanted playgrounds; some wanted places for baseball, basketball and tennis. That is why there is a little of everything along the length of the four miles of the park. The decision to include bicycle and walking paths was an important decision. There were not as many bicyclists in the 1980s as there are today, but the planning groups agreed that a bicycle route would be a good idea.

The park has won many awards for its thoughtful design and for the strong role of neighborhood groups in designing the project.

In both the Emerald Necklace and the Southwest Corridor Park, the tradition of neighborhood involvement continues. Many of the park activities and park improvements are led by neighborhood-based non-profit groups who bring together volunteers and community donations to work in the parks.

Visit the Southwest Corridor Park on a Saturday morning, and you may see groups of neighbors planting flowers and pushing wheelbarrows filled with compost and mulch. Visit the Emerald Necklace and see volunteers planting wildflowers or working on a clean-up along the shores of the river. Behind the scenes, volunteers meet in community meetings to study the needs of the parks and work with the city and state agencies. Each year, thousands of hours of volunteer energy are contributed to the parks. Volunteers choose this work because it is a way to enjoy time in nature and because it is a way to help bring neighbors together to build a stronger and healthier city.

- Video #2: The Economics of Public Goods

VIDEO SCRIPT #2: The Economics of Public Goods

Suppose that you walk down a city sidewalk and write a list of 20 things that you see, including things that you normally just take for granted. Here’s an example.

1. Sidewalk

2. Curbstone

3. Street

4. Storm drain

5. A maintenance hole cover that says “Water Department”

6. An old-fashioned sidewalk clock on a stand

7. Bank

8. Convenience store

9. Yoga studio

10. Pizza restaurant

11. A bench in front of the pizza restaurant

12. A planter with flowers in front of the pizza restaurant

13. Office building with a sign offering free job training

14. Fire station

15. Public park

16. Benches in the public park

17. Flowers in the park

18. Trees in the park

19. Squirrels

20. Birds

Think about some of the things that you take for granted. Who put them there? Who benefits from these simple things that we take for granted? In this lesson we look at the economic concepts of “public goods” and “private goods” and at three types of organizations that provide products and services in the city: private, public and non-profit.

Some of the places on this list are privately-owned businesses, including the pizza restaurant, yoga studio, convenience store and bank. Someone – a person, a family, a partnership, or other group – started these businesses and runs these businesses, offering products and services to the community. Customers pay for the products and services. Customers buy pizza. Customers sign up for and pay for yoga classes. Customers buy food from the convenience store. The owners and workers earn money from these businesses.

Other things on your list are probably not provided by a private business. Think about the storm drains that you see along the side of the street. Storm drains are a necessary part of a city street, to provide a place for rainwater to flow after a rainstorm and a place for snow to melt in the winter. But no one would say “I think I’d like to set up a storm drain” the way they might say “I would like to open a pizza restaurant” or “I want to open a yoga studio.”

Why not?

In the study of economics, a PUBLIC GOOD is defined as something that benefits everyone, but it would be hard to get people to be customers to pay for that item.

A public good is something that is benefits everyone, no matter whether or not they own it; or no matter whether or not they helped to pay for it. It is something that can’t be divided into slices or shares, so that it would be hard to charge for each person’s share of the benefits.

Storm drains are a good example. Everyone benefits, but no one chooses to pay for a storm drain the way they would buy a slice of pizza or sign up for a spot in a yoga class. Public goods are typically provided by government, paid for by the taxes that everyone pays to the government.

Trees and flowers in a public park are also great examples. Everyone enjoys seeing the trees and flowers, and everyone breathes air that is cleaner because the city has trees. Everyone enjoys seeing and hearing birds that live in the trees. It doesn’t matter how many people look at and enjoy the trees and flowers and birds. Unlike a slice of pizza or a spot in a yoga class, you can’t claim these things as your own.

The fire department is another example of a public good. The fire department protects all the houses and businesses in the city, even when you don’t need to call them.

Sidewalks and streets are also public goods. These benefit everyone and can’t be divided up and sold like a pizza, to say, for example, “this square of this sidewalk is mine.”

What types of organizations provide the products and services that you noticed on your walk in the city?

We can define three types of organizations:

Private sector – businesses owned by individuals, families, partnerships and corporations, providing products and services and earning profits for the owners. A profit is defined as earnings that are extra,… for example that money earned by the pizza restaurant that is extra after paying for the pizza ingredients, the wages for workers, the rent for the building, and the other costs. The private sector is also sometimes called the "for-profit" sector.

Public sector – Public sector organizations are agencies or departments in the local, state or federal government or other levels of government. The parks department, roads department, fire department, and other city departments are part of the public sector. There are different levels of government that make up the public sector. There are city parks, state parks, and national parks, each provided by the different levels of government. There are local roads, state highways and interstate highways, paid for and maintained by local, state and federal government.

Non-profit sector – Non-profit organizations are developed to provide important services to the community. Non-profit organizations are organized by people from the community. Unlike private sector organizations, they are not designed to make a profit, but just to bring in enough money to provide the services that they offer In the list of 20 things that you saw on a walk through the city, there was an office that offered free job training. That office may be a non-profit organization, developed to help people in the community to learn new skills and find new jobs. Non-profit organization provide services free or at a low cost, not to earn profits, but to make the community a better place.

Most of the places and things on the list of 20 things come from the private, public or non-profit sector. But here are two more categories:

Informal sector – some organizations are informal, without paid staff or budgets or profits. For example, if you saw a group of neighbors having a park clean-up day, that might have been simply an informal neighborhood organization, not a private business, not a public government organization, and not a non-profit organization.

Non-economic – Look back at the list of 20 things you saw on a walk through the city. The last two items – birds and squirrels – are not part of the economy of the city – they are not products or services.

Who provides public goods? Parks, streets, sidewalks, storm drains, fire departments, and other PUBLIC GOODS are usually provided by the public sector. Each of these things might be provided by the local government, the state government, or the federal government.

There are a few exceptions that are interesting to think about. We listed a bench in the public park, and we assume that is a public good, placed there by the city government as part of the public park. We listed flowers in the public park also, also public goods. But we also listed a bench and flowers in front of the pizza restaurant. It is hard to say whether these are private or public goods, since they mostly benefit the customers of the pizza restaurant, but also benefit everyone.

Another example: the sidewalk clock is there for everyone who walks by. Especially in generations before cellphones, it was great to have a clock on the city street so you could see the time. The sidewalk clock is a public good, but not necessarily provided by the city government. A local business such as a bank often provides a sidewalk clock, just a way of advertising the bank name while giving back to the community.

In any college textbook about economics, we see the concept of public goods, and learn that most public goods are provided by government agencies, through taxes, because there is no real incentive for individuals or private businesses to provide these things. But when we study civic engagement we also see that many individuals and private sector businesses help to support things like parks, by volunteering, donating money and serving on committees, even though they don‘t earn any money for this work. As you study the idea of civic engagement, it is helpful to think about why people and businesses are willing to give time and money to support things like public parks.

Here is a challenge: Look at photos of a city street or take a walk along a city street and make your own list of things that you see. How many public goods can you find in your list? Can you include things that are invisible, such as clean air or shade from trees? Can you include some things that are taken for granted such as signs and traffic lights? Who in the community takes care of these things?

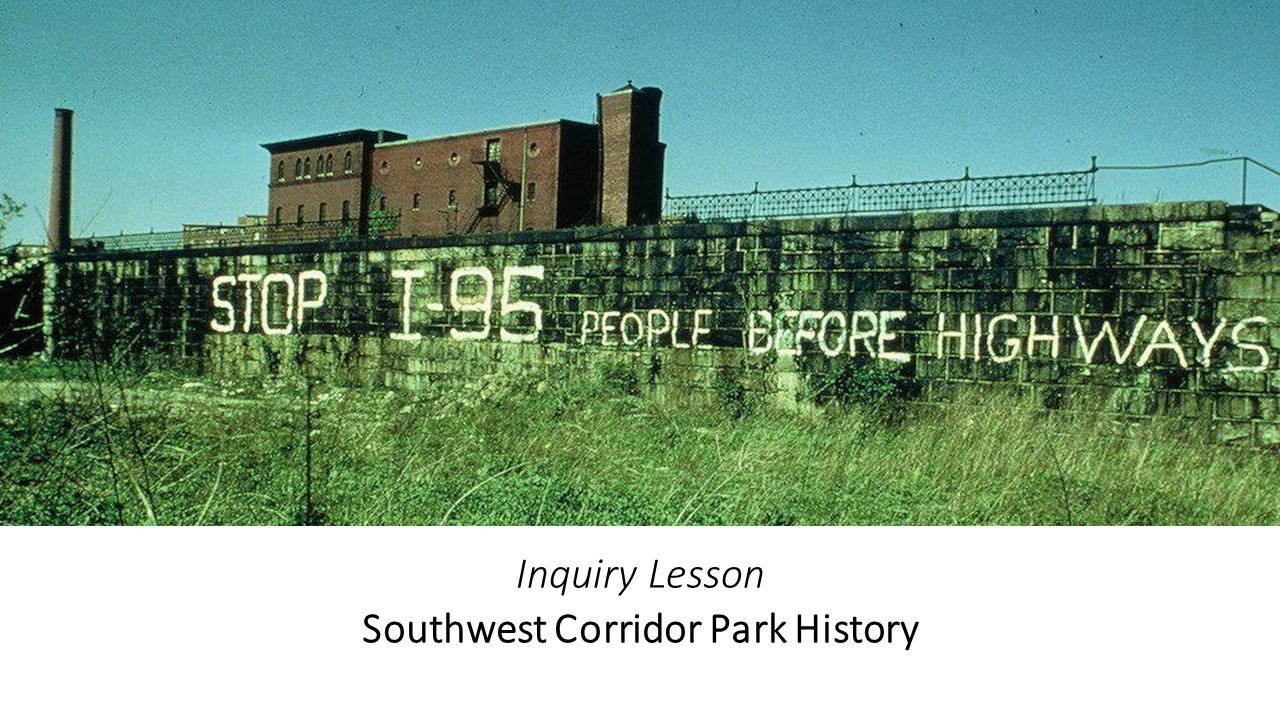

- Inquiry Lesson: Primary and Secondary SourcesThe following slide presentation provides a collection of primary and secondary sources.

-

Web Link: Inquiry Lesson - Primary and Secondary Sources (PowerPoint) - Timeline: Southwest Corridor Park History1948:

A Regional plan is proposed which envisions an expressway along the Southwest Corridor, as part of the Interstate network of highways

1962:

A plan is developed by the state to build I-95 as a 12-lane elevated expressway through Jamaica Plain and Roxbury, as well as an Inner Belt through Lower Roxbury and Fenway into Cambridge.

1966:

The anti-highway movement begins in Cambridge and the demolition begins in Boston. By the end of 1973, more than 500 buildings are demolished.

1969:

A demonstration at the State House brings together highway opponents from various Boston neighborhoods as well as environmental groups

1970:

Governor Francis Sargent, in response to neighborhood and environmental opposition, stops the highway project to begin the Boston Transportation Planning Review restudy.

1971:

The South End convinces Mayor Kevin White to halt plans for the South End By-Pass

1972:

Neighborhood plans for redevelopment of cleared land is vital in convincing Governor Sargent to cancel plans for highway in Southwest Corridor

1975:

Massachusetts becomes the first state to cash in highway funds for mass transit under new federal funding act, which provided Urban Mass Transit Administration (UMTA) funding for Southwest Corridor

1980:

Construction of the new Southwest Corridor project begins, and neighborhoods plan details of park and redevelopment of cleared land

1987:

Opening of the new Orange Line

1989:

Dedication of Southwest Corridor Park - Reading: Understanding Civic EngagementUnderstanding Civic Engagement

Stories about civic engagement can be inspiring. A group of teens see an underused section of a park and propose that it be transformed into a community garden. They write letters to elected officials, hold community meetings, get approval, sponsor a fundraising drive, and then it is time for clean-up and construction work, and soon everyone is celebrating the new garden.

Sometimes a community project is that simple. But more often, the work is not always simple, and often there is a much longer process, with setbacks and complications, and with many long meetings and periods of waiting.

If you ask people who have been active in community work for many years for examples of projects that were simple and successful, they will have some good stories. If you also ask for examples of projects that moved slowly with only small successes, they will also have many examples. This part of the lesson looks at some myths and realities of civic engagement.

The story of the People Before Highways movement that resulted in the Southwest Corridor Park is one of those inspiring stories. Every citizens group and every neighborhood that was involved in that movement continues to tell the story with pride, sharing the story that “we stopped the highway.” The heroes of that moment were people from all neighborhoods, races, backgrounds and roles, who met and spoke up and organized. The most famous moment in that work came in 1970, with the People Before Highways march on the State House. Following that moment, another hero of this work was the newly inaugurated governor, Francis Sargent, who had been a long-time advocate for highway building, and who, after hearing from the demonstrators, stated very simply “we were wrong” and moved forward with public transportation and parkland along the corridor instead of the highway.

But between the decision to stop the highway plans and the opening of the new park, there was a period of almost 20 years of planning and construction. When the park finally opened, park planners described thousands of hours of community meetings. The park was designed by the hard work of city planners working with multiple neighborhood groups. Community meetings were sometimes exciting forums for sharing ideas and vision for the new corridor. But many of the meetings were less-than-exciting, with lots of behind-the-scenes work by city planners and engineers, contract negotiations with builders and landscapers, and much more. Some community meetings were just updates about the progress of different phases of the project, forums for complaints about the impact of construction, or long discussions about where to put a particular fence or park entrance or subway vent.

This lesson presents myths and realities about civic engagement. As you read, see if you can think of examples of these myths and realities from history, from current events, or from your knowledge of community work in your city or neighborhood.

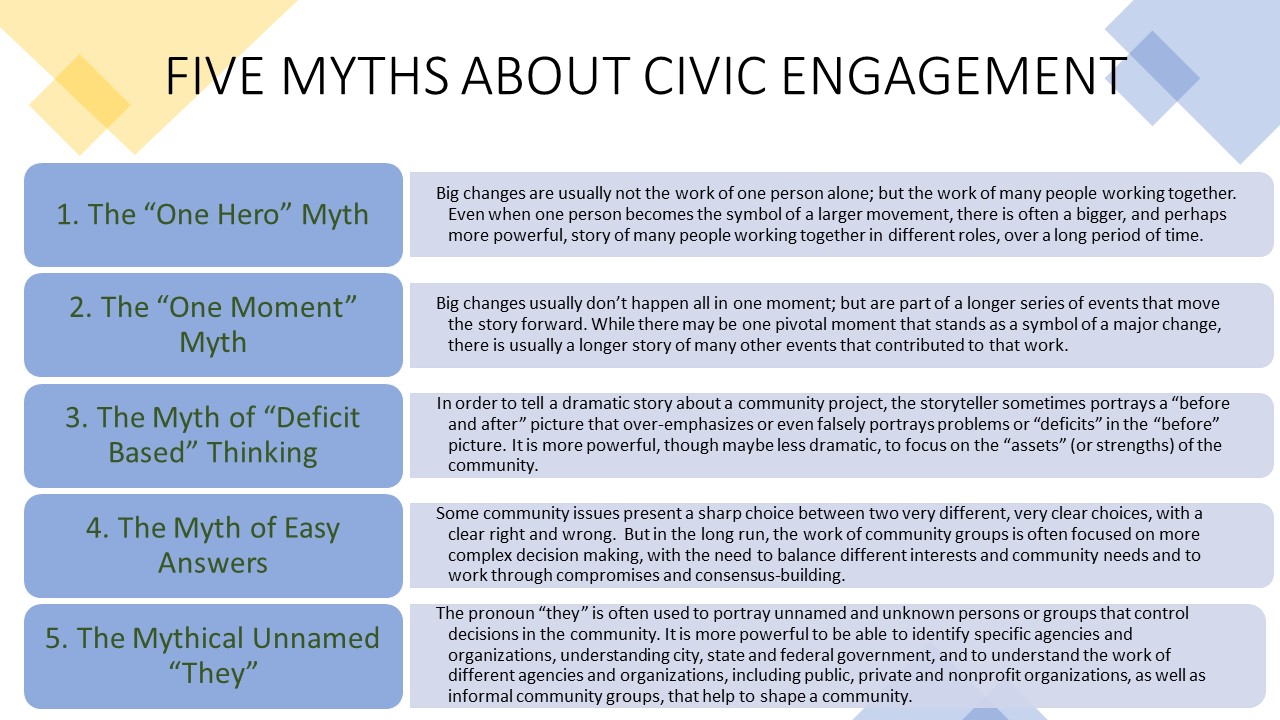

FIVE MYTHS ABOUT CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

1. THE ONE-HERO MYTH. Big changes are usually not the work of one person alone; but the work of many people working together. Even when one person becomes the symbol of a larger movement, there is often a bigger, and perhaps more powerful, story of many people working together in different roles, over a long period of time.

2. THE ONE-MOMENT MYTH. Big changes usually don’t happen all in one moment; but are part of a longer series of events that move the story forward. While there may be one pivotal moment that stands as a symbol of a major change, there is usually a longer story of many other events that contributed to that work.

3. THE MYTH OF DEFICIT-BASED THINKING. In order to tell a dramatic story, the storyteller sometimes portrays a “before and after” picture that over-emphasizes or even falsely portrays problems or deficits in the “before” picture. For example, have you ever seen a movie about a school that was terrible, where “no one cared” until one heroic leader came along and changed everything? That type of story combines the myth of “one hero” and the myth of “one moment” of change, and the myth of “deficit-based” thinking. A more complicated, but more powerful, story focuses on the assets of the community. An asset-based story might not make as good a movie, but is a more powerful story: “Here is a school where parents and local businesses are very supportive, and children and teachers work hard and care about their school. We had some challenges in the school and so we worked together and improved the school through community effort.”

4. THE MYTH OF EASY ANSWERS. Some community issues present a sharp choice between two very different, very clear choices. But in the long run, the work of community groups is often focused on wider view of neighborhood planning, making room for different interests and community needs, and working through compromises and consensus-building. This work often involves learning about behind-the-scenes information about budgets, construction costs, civil engineering, urban design, architecture, landscape design, local geography and environmental conservation.

5. THE MYTHICAL UNNAMED “THEY.” Have you ever heard someone complain that “’they’ want to put a highway right through this neighborhood” or “’they’ don’t care about the parks in this neighborhood.” or “’they’ only care about building luxury housing.” The pronoun “they” is often used to portray unnamed and unknown persons or groups. It is more powerful to be able to identify specific agencies and organizations, understanding city, state and federal government, and different branches of government, and different agencies and organizations, including public, private and nonprofit organizations, as well as informal community groups, that help to shape a community.

As a challenge:

[1.] Using the list of “five myths” as inspiration, write your own list of “five realities” or “myths and realities” or “do’s and don’ts” for civic engagement.

[2.] Watch the video “Federal, State or Local” to learn more about the differences among these three levels of government.

[3.] The history of the Emerald Necklace is a great story with many different angles to the story. Look at these opening paragraphs from three versions of this history. After reading each one, answer the question: whose vision created the Emerald Necklace? What differences do you notice among the three different sources of this history? After reading all three, how would you tell the story of the creation of the Emerald Necklace?

[a.] From Boston Magazine "Landmarks" series:

As you traverse the seven-mile-long series of meadows, marshlands, and roadways, you’re living out the vision of Frederick Law Olmsted. The country’s first professional landscape architect, Olmsted believed city parks should be sanctuaries from the clamor and grit of urban life, providing peaceful settings and picturesque views as a contrast to their industrial surroundings. When Olmsted successfully applied this design theory to New York’s Central Park in 1857, Boston took note, eventually hiring him in the 1870s to build not just one large park, but an entire park system.

https://www.bostonmagazine.com/property/2018/05/15/emerald-necklace-boston-history/

[b.] Boston Urban Planning Website

In the late 19th century, a citizens’ group petitioned to the city to reserve space for public parks to encourage community and a sense of identity to public space. In response to the public’s petition, the City of Boston created a Park Commission to be responsible for two key agendas: first to establish a park system and second to fix the sewage problem occurring in Back Bay. Without any delay, the Park Commission sought help from the distinguished landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted.

Quoted in: https://bostonurbanplanning.weebly.com/emerald-necklace.html

________________________________________

(c.) From the National Parks Service history lesson plans:

In 1870, the city of Boston was an overcrowded, noisy, and dirty place. Its population had expanded rapidly because of the Industrial Revolution, and the peninsular port city was crammed with buildings and people. Many of the people who lived in the crowded city did not have the opportunity to travel to the country for fresh air and relaxation. In 1875, the Boston City Council passed a Park Act to help address these concerns. The park commissioners turned to Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who had created New York City‘s Central Park, to plan a park system for the city that would provide residents with an opportunity to enjoy the benefits of nature.

Frederick Law Olmsted believed that planned parks and open spaces improved the health and disposition of those who endured the claustrophobic and often unsanitary conditions of city life. For Boston, he envisioned a "Green Ribbon" of parks that would encircle the city. Such a system would suit the geography of Boston as well as allow easier access to nature than one large central park. Over the next several years, he and his firm would create and weave together a series of parks that became known as Boston‘s Emerald Necklace.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-emerald-necklace-boston-s-green-connection.htm - Video #3: Federal State or Local

Video Script #3: Federal, State and Local

As a community member engaged in community projects, you gradually become more and more aware of the different levels of government that help to shape the community.

In the United States, the main levels of government are:

the federal government – meaning the national level government...

the state government....

and the local government, meaning the city, town or county government.

As we are focusing on parks and greenspaces in our community – notice that all three levels of government provide systems of parks:

The Boston Freedom Trail is a national park...

There are many major state parks, including the Southwest Corridor, the Charles River, and parts of the Emerald Necklace...

And as you look at maps of all the parks in the city of Boston, you see that most of the more than nine hundred parks are city parks.

The United States is different from many other countries, with a history of keeping most government services and programs (parks, roads, schools…) and most government decision-making at the local and state levels.

That tradition stretches back to the American Revolution, when the 13 colonies wanted to form a loose federation, to work together, but also to maintain some of their own decision-making and some independence.

The roles and responsibilities of the federal, state and local government have changed over the past centuries, from the first 13 states to the present, but still with an emphasis on keeping most government services and decisions at the state and local level.

In the United States, it is very typical for the federal government to set overall goals and plans for the country, and to provide money to state and local governments to carry out those goals.

In the story of the construction of the Southwest Corridor Park, we saw an example of this model.

In 1948, the federal government created a plan to build a network of highways all over the country.

But the federal government did not plan to directly build the highways. The federal government offered money, from gas taxes and other taxes, to the states, so that the states could build these highways.

At first, the state government in Massachusetts agreed with these plans, and studied and planned to build a new system of highways through Boston, Cambridge and Brookline. The federal government would provide 90% of the money for the project, and the state government, through state taxes, would only have to pay 10%.

But then the people in neighborhoods of Cambridge, Brookline and Boston started to learn about the highway plans.

They saw how disruptive similar highways were in other cities.

Neighborhood groups from all the affected areas began to protest.

Eventually the mayor of Boston added his voice to this movement.

And in a dramatic turn-around, the governor of Massachusetts, Governor Francis Sargant, who had always been a supporter of highway development, listened to the protests. He announced that “we were wrong” and started the process of cancelling the highway plans.

The next event was even more amazing.

Through work in Washington D.C., the federal highway department changed the laws, and allowed federal highway money to be used for public transportation projects instead. The Southwest Corridor Park was the first project anywhere in the country to use federal highway money to create public transportation, parkland and even a bicycle path, creating a corridor for environmentally-friendly active transportation instead of highways.

The work was done by Massachusetts state agencies, and was mostly paid for with federal highway money.

Imagine being a member of one of the neighborhood groups in those days. You would have gradually worked to figure out the different layers of decision making, to find out who decides what gets built in your city. You would see how a federal government plan was adopted by the state and was going to affect you in your city. And how local protests changed state policy and eventually transformed federal policy.

How do community members learn about the different levels of government? Some of this information comes from reading about how the U.S. government is organized. Some comes just from experience, of figuring out who manages the different projects in your community.

Fast forward to the present. Today, the network of park volunteers who help to take care of the Southwest Corridor Park have learned to work with a mixture of local and state agencies along the park.

The Southwest Corridor Park follows the route of the MBTA orange line. The MBTA is a special division of the Massachusetts state government.

Because the MBTA owns the land along this corridor, the Southwest Corridor Park is a state park, under the care and control of the state parks agency, which is called the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR).

Now let’s make the story more complicated. The state parks agency, DCR, takes care of the parkland.

Now let’s make the story more complicated:

The state parks agency, DCR, takes care of the parkland. But when the bike path crosses streets, it is the local City of Boston transportation department that is responsible for the crosswalks, traffic signals, and curb cuts.

Who provides public safety in the park? Because it is a state park, it is the Massachusetts State Police, not the Boston Police Department, that patrols the park.

But Boston Police also help out, and in fact they sponsor police-community basketball games and special events in the park every summer. The MBTA Transit Police also help out, since there are eight orange line stations along the park. The Northeastern University police (which is a private, non-profit university, not part of the state or local government) also patrols the sections of the park near the university. Several times per year, the Northeastern University police often serve coffee and hot chocolate along the bike path as a special event to meet community members who use the bike path.

Here is another example of this complexity. When it snows, DCR shovels the bicycle paths, except for some paths that are city sidewalks, which are shoveled by the city public works department.

And except for the areas around the MBTA stations, which are shoveled by the MBTA.

The Northeastern University maintenance department also shovels a section of the path. Did you know, the agencies hold a snow summit every fall to meet together to review the map of who shovels snow where.

So it’s complicated, but interesting to figure out the different agencies and levels of government. Sometimes there are serious debates about what decisions should be made at the local, state or national level. Other times it is just interesting to figure out who does what in your community. Consider this one of the responsibilities of an actively engaged community member, one of the many things that you learn along the way.

Tags = government | civic-literacy | community | local history | parks-and-greenspace | Subject = History | Grade Level = MS | Time Period = School Year | Program/Funding = | NONE |

Direct website link to this project: http://ContextualLearningPortal.org/contextual.asp?projectnumber=765.3735

|